Before he became a founding father of the United States, Benjamin Franklin established one of America’s first volunteer fire departments. His name appears on a recently discovered list of the brigade’s members, thought to have been written 276 years ago.

Politician, printer, inventor, diplomat, author, scientist—Benjamin Franklin will forever be remembered as a man of many talents. But not everyone knows the founding father was also a volunteer firefighter who at age 30 established Philadelphia’s first fire department. Tom Lingenfelter, president of the Heritage Collectors’ Society in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, recently announced his discovery of a relic from this fascinating phase of Franklin’s career: a document listing his name and those of the Union Fire Company’s other members, thought to date to 1736.

Born in Boston in 1706, Franklin left home and moved to Philadelphia at age 17. His adoptive hometown still bears numerous traces of his extraordinary legacy, from the University of Pennsylvania to America’s first lending library, the Library Company of Philadelphia. One of the city’s most central and successful public figures from a very young age, Franklin cofounded the Union Fire Company, an all-volunteer brigade, in 1736.

“When Franklin starts the volunteer fire department in 1736, he’s sort of an up-and-coming guy,” said Libby O’Connell, HISTORY’s chief historian. “He’s working his way up the rungs of civil and professional life. By founding the volunteer fire department in Philadelphia, he’s setting himself up as a civic leader.” He was likely inspired by America’s first professional fire department, established in his native Boston in the 17th century, O’Connell explained.

Tom Lingenfelter image |

The men of the Union Fire Company, totaling about two dozen, pledged to hasten to the scene should a fire break out in a fellow member’s home. Their equipment consisted of leather buckets for dousing flames with water and linen bags for spiriting valuables out of burning buildings. Like the many other mutual benefit organizations cropping up around the same time, the volunteer fire department offered members an opportunity to improve their city and themselves, O’Connell said. “It’s a strain of American culture you see lasting past the Revolution,” she explained. “You don’t just look to the government; you have to look to your community to pitch in and help. Franklin was really at the forefront of that.”

Active until 1820, the Union Fire Company motivated other groups of people across Philadelphia to open their own volunteer brigades, O’Connell said. These types of associations, formed by individuals who chose to help each other for the good of society, would eventually set the stage for professional organizations and raise standards of living across America. The same spirit can still be seen in volunteer fire departments today, she noted.

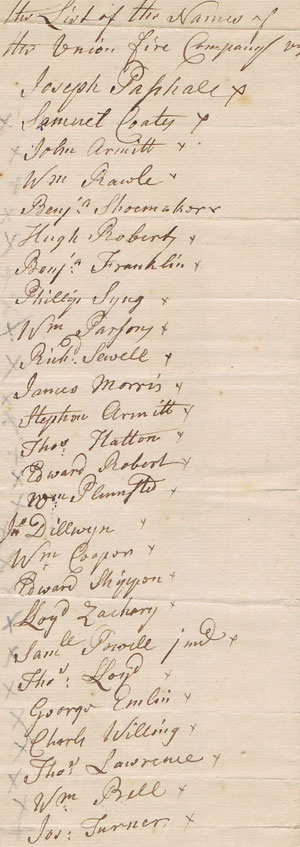

Lingenfelter came across the list of Union Fire Company members while sifting through his enormous collection of historical manuscripts. “It got my attention when I saw Ben Franklin’s name on the list,” Lingenfelter said. “It was in a pack of old business papers, and I don’t remember where I got it.” He said the papers seem to have belonged to Union Fire Company cofounder Joseph Paschall, a prominent merchant and member of Philadelphia’s Common Council. Paschall, whose name appears first on the roster, served as the fire brigade’s clerk.

Roughly 10 inches long and 4 inches wide, the paper features the names of 26 men, scrawled in ink under the heading “The List of the Names of the Union Fire Company.” Each name is marked with Xs in pencil and pen, an indication that the list might have functioned as an attendance sheet.

By comparing the collection of names to the Union Fire Company’s book of minutes, Lingenfelter concluded that the document dates to 1736, the year of the department’s founding. He said that the group’s rules, also recorded in the minutes, offer a potential reason for the list’s existence: Each member was required to keep two copies of the roster. This particular copy likely belonged to Paschall and appears to be in his handwriting, Lingenfelter said.

In addition to Franklin and Paschall, members listed in the document include William Rawle, a lawyer and abolitionist who served as U.S. district attorney for Pennsylvania after independence; Edward Roberts, a colonial mayor of Philadelphia; Richard Sewell, a merchant and sheriff; and Philip Syng, a renowned silversmith who made the inkstand used to sign the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

Lingenfelter said he has no immediate plans for the document, which has yet to be analyzed and authenticated. And while it may not provide new information about the Union Fire Company, it serves as a reminder of Benjamin Franklin’s numerous accomplishments and a fascinating project that typified his notion of civic responsibility. “His record on that type of public service was unbeatable,” said O’Connell.

By: JENNIE COHEN / history.com |

|

![]()